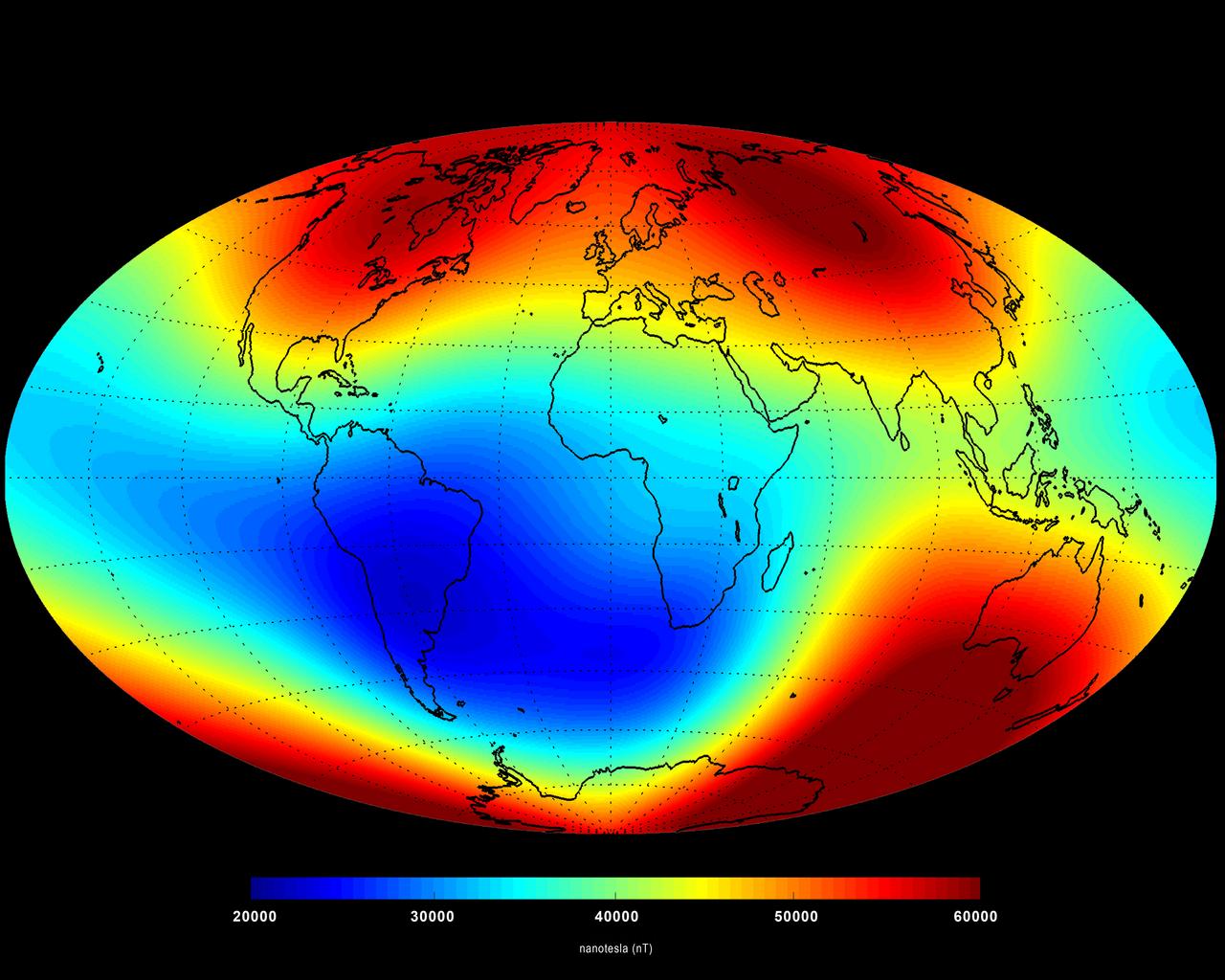

NASA is actively monitoring a strange anomaly in Earth's magnetic field: a giant region of lower magnetic intensity in the skies above the planet, stretching out between South America and southwest Africa.

This vast, developing phenomenon, called the South Atlantic Anomaly, has intrigued and concerned scientists for years, and perhaps none more so than NASA researchers. The space agency's satellites and spacecraft are particularly vulnerable to the weakened magnetic field strength within the anomaly, and the resulting exposure to charged particles from the Sun.

The South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) - likened by NASA to a 'dent' in Earth's magnetic field, or a kind of 'pothole in space' - generally doesn't affect life on Earth, but the same can't be said for orbital spacecraft (including the International Space Station), which pass directly through the anomaly as they loop around the planet at low-Earth orbit altitudes.

During these encounters, the reduced magnetic field strength inside the anomaly means technological systems onboard satellites can short-circuit and malfunction if they become struck by high-energy protons emanating from the Sun.

These random hits may usually only produce low-level glitches, but they do carry the risk of causing significant data loss, or even permanent damage to key components - threats obliging satellite operators to routinely shut down spacecraft systems before spacecraft enter the anomaly zone.

Mitigating those hazards in space is one reason NASA is tracking the SAA; another is that the mystery of the anomaly represents a great opportunity to investigate a complex and difficult-to-understand phenomenon, and NASA's broad resources and research groups are uniquely well-appointed to study the occurrence.

"The magnetic field is actually a superposition of fields from many current sources," explains geophysicist Terry Sabaka from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The primary source is considered to be a swirling ocean of molten iron inside Earth's outer core, thousands of kilometres below the ground. The movement of that mass generates electrical currents that create Earth's magnetic field, but not necessarily uniformly, it seems.

A huge reservoir of dense rock called the African Large Low Shear Velocity Province, located about 2,900 kilometres (1,800 miles) below the African continent, disturbs the field's generation, resulting in the dramatic weakening effect - which is aided by the tilt of the planet's magnetic axis.

"The observed SAA can be also interpreted as a consequence of weakening dominance of the dipole field in the region," says NASA Goddard geophysicist and mathematician Weijia Kuang.

"More specifically, a localised field with reversed polarity grows strongly in the SAA region, thus making the field intensity very weak, weaker than that of the surrounding regions."

While there's much scientists still don't fully understand about the anomaly and its implications, new insights are continually shedding light on this strange phenomenon.

For example, one study led by NASA heliophysicist Ashley Greeley in 2016 revealed the SAA is drifting slowly in a north-westerly direction.

It's not just moving, however. Even more remarkably, the phenomenon seems to be in the process of splitting in two, with researchers this year discovering that the SAA appears to be dividing into two distinct cells, each representing a separate centre of minimum magnetic intensity within the greater anomaly.

Just what that means for the future of the SAA remains unknown, but in any case, there's evidence to suggest that the anomaly is not a new appearance.

A study published last month suggested the phenomenon is not a freak event of recent times, but a recurrent magnetic event that may have affected Earth since as far back as 11 million years ago.

If so, that could signal that the South Atlantic Anomaly is not a trigger or precursor to the entire planet's magnetic field flipping, which is something that actually happens, if not for hundreds of thousands of years at a time.

Obviously, huge questions remain, but with so much going on with this vast magnetic oddity, it's good to know the world's most powerful space agency is watching it as closely as they are.

"Even though the SAA is slow-moving, it is going through some change in morphology, so it's also important that we keep observing it by having continued missions," says Sabaka.

"Because that's what helps us make models and predictions."

Ingen kommentarer:

Legg inn en kommentar

Merk: Bare medlemmer av denne bloggen kan legge inn en kommentar.